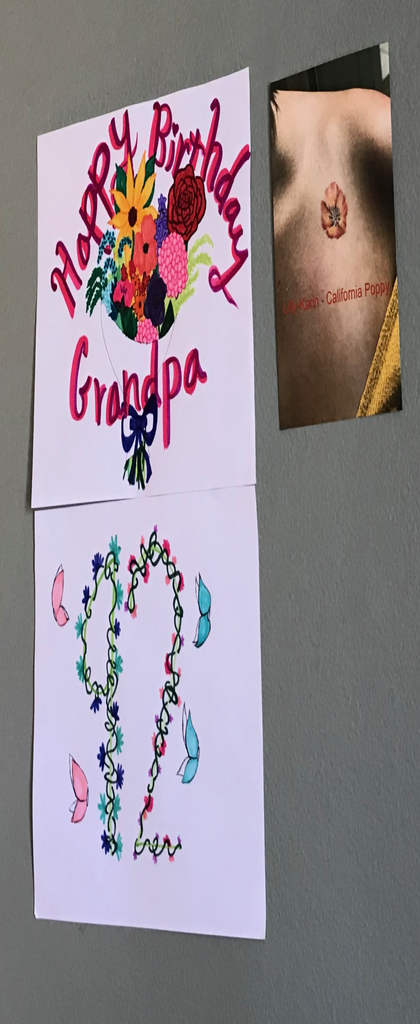

My father turned 92 this past weekend, and I spoke to him via FaceTime. The next day, I showed up in person with a card made by my daughter. I’d reminded her that even with his glasses, her grandfather couldn’t see very well, so she should use large lettering and lots of colors.

When I got there, I found other birthday cards and notes, but most were still in their envelopes, or tucked under articles of clothing. So I used some putty to tack Lilly-Karin’s mini-poster on the wall, next to the photo of her tattoo, where he could easily see it.

During my visit that day, and the next, his gaze would drift toward the wall, and he’d remark that “now we knew for certain” he was 92.

The next day, I arrived with my wife, and Frank was napping. As soon as I moved a chair close to the bed, he woke and asked about the news. “What’s happening?”

I gave the usual response: the weather, COVID-19, only a month until L-K leaves for college. He sat up a bit. “But what about the BBQ?”

I thought he was referring to the brick BBQ setup back at their house, the one built adjacent to the deck. I replied that it was basically covered since no one was using it this summer. And that once he passed, we’d probably give his equipment to my niece and her husband, since they were definitely fans of BBQ and outdoor parties. Whoever buys the house gets the rest.

No, he said, what’s happening with Santa Maria BBQ? Had there been any news about Santa Maria BBQ in the paper? I looked at my wife, who shrugged. I replied honestly that I hadn’t seen any news, or read anything online or heard mention on the Food Network.

He leaned back and contemplated the wall. “There’s a real opportunity there. You should buy it.”

Buy Santa Maria BBQ? You mean, like, the copyright and the recipe?

Yes, he said. “You could make a lot of money.”

And there it was. For years my father has worried that he wouldn’t earn enough money to see himself through retirement, or take care of his family after his death. He has put money into some dubious investments, and tried to patent a number of ideas all with an eye toward making the Big Score. He didn’t want to be wealthy, per se. He just wanted to have the financial freedom to be able to do what he wanted.

We talked a bit more about the BBQ gambit, and I assured him that I didn’t have the investment capital for such an undertaking, nor was I particularly interested in trying to corner the market on red oak-fired tri-tip beef.

I also assured him that there was enough money in his retirement accounts to take care of my mother once he passed. If we downsized and watched expenses, things would be fine. That seemed to help.

At the end of his life, my father was trying to have one more success, or at least sock away some cash. It’s okay, Dad. You did what you could.

Which is the most any of us can do.