The 2024 Nebula Conference was held this month in Pasadena, which is a ridiculously short flight away (Oakland—Burbank), so I bought a ticket and signed up to volunteer. Decided to pass on the banquet due to $$. (Later, I was given a dinner ticket by mistake and they refused to take it back. Free rubber chicken!)

But the week before the event was a confluence of DayJob stress, side effects from my prescription, and the death of a friend, Gabriel de Anda. Since Gabriel was one of my three oldest friends who still lived in the greater Los Angeles area, I had planned to see him. It had been a few years. Plague, political fuckwits, and contracting chaos had all contributed to the situation.

It’s a pretty poor excuse in retrospect. The constant distraction of Mundane Reality is, well, distracting. You talk with friends, or see them on Zoom, but if they’re more than a hour or two away by any sort of transit, any plans for sitting down to eat freshly grilled fish and drink pisco sour never come to fruition.

Then that bastard cancer drops by and well, bad things happen. Sometimes they happy really fast. I had just emailed Gabriel to confirm his physical address so I could drop a graduation announcement in the mail. Oh, and I was going to be in Pasadena the following weekend. Maybe we could get together.

He responded immediately. Said he’d been in the hospital for two weeks and was now home under hospice. Some kind of unknown cancer. He expected to be gone in a few days and was starting to say his goodbyes.

WTF? WTAF? I mean, he was doing edits on a story promised to a pro SF magazine. This was a totally shitty time to die. (Yes, there’s rarely a good time.)

I almost canceled my plans. Looked into a last-minute flight and hotel, but couldn’t put it together. (Migraines are a grand thing, aren’t they?) I hoped that Gabriel would still be around in a week when my brain was back online and I was within striking distance.

He wasn’t. Three days after we corresponded about literary estates and my possible contribution of an afterward to his story, his widow posted the news of his passing.

Shit.

So I went to the Nebula Conference in a weird fog. While it was truly good to see a few friends, it was also good that the panels were being streamed and recorded because I hid out in my room. A lot. I threw myself into a new flash story for a contest with a painfully short deadline. I slept more than usual.

Then I saw that my latest podcast story had dropped (“There are Worse Travel Companions” – Sudden Fictions). The story is about a man who works in an orbital crematorium. It’s a brief conversation about how we treat the remains (cremains) of loved ones.

The synchronicity wasn’t pleasant.

Fortunately, I have two dear friends, Tash and Dan, who live in the greater LA/Orange County. I saw them both last weekend. Gave them books. Talked their ears off. Hugged and was hugged in returned.

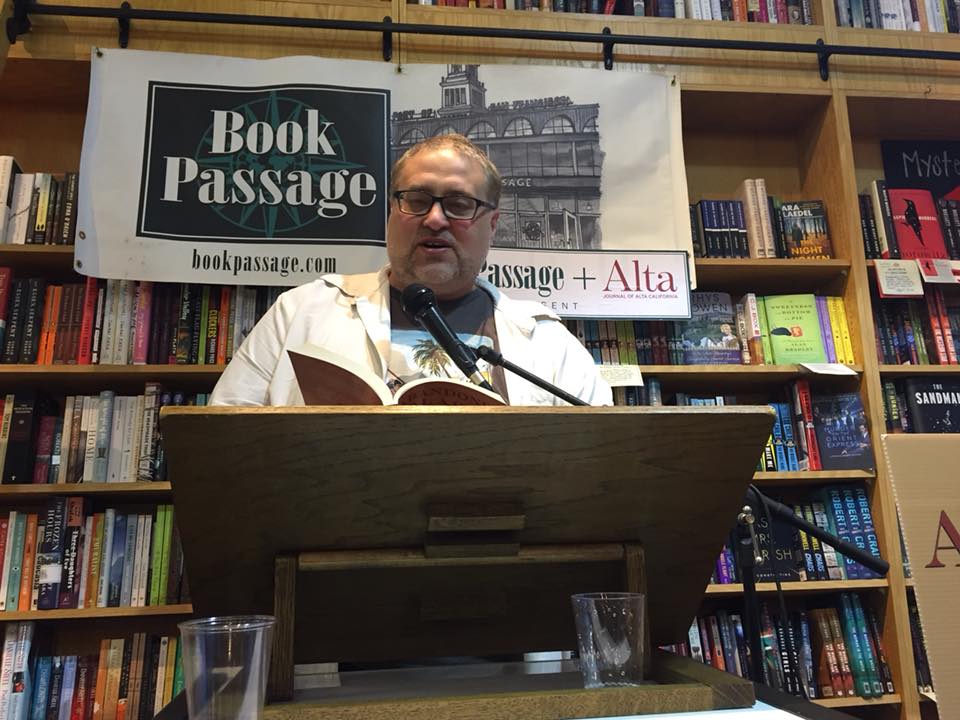

It struck me at one point that all four of us had shared only one experience: my wedding. Here’s Gabriel back on that day in 2000:

I like to think his mind was filled at that moment with its usual urbane and clever thoughts. In addition to being an attorney fighting for the underdog, Gabriel was a writer of lush, poetic SF. He was one of my first students in a continuing ed course of “Writing the Fantastic” or some-such. After the class ended, we became friends, trading letters and story drafts for three decades.

Our styles were nearly opposite. He sometimes compared my writing to a zen garden, clean and focused (ha!), while his writing felt more like a swirl of ants trying to find a scent trail. My advice to him usually boiled down to Whoa there, partner. Do you really think you need three adjectives to describe that thing? Pick the best one. But Gabriel was a baroque artiste who believed in good excess. He loved Ridley Scott and Gaudí, William Gibson and secret interstellar societies, good coffee and street art.

He read everything I published (and some things I didn’t) and asked me repeatedly when was I going to write a novel. When I retire, I answered. Don’t worry, you’ll get a chance to see the first draft.

Damn.

So tomorrow I will go back into the word mines and chip away at a new vein, because someone has to tell the story.

Adios mi amigo. Adios.